Time moves slowly with the Maasai. It moves slowly in a way that I have never quite experienced before. There is an overwhelming sense of peace. Everyone moves at their own pace and that pace is dictated around social ties and survival necessities. I felt so grounded there. I felt like I had a purpose there. The days were intense, the sun blistering my skin and the sweat soaking my clothes, but we were all in it together in this kind of beautiful synchronised movement.

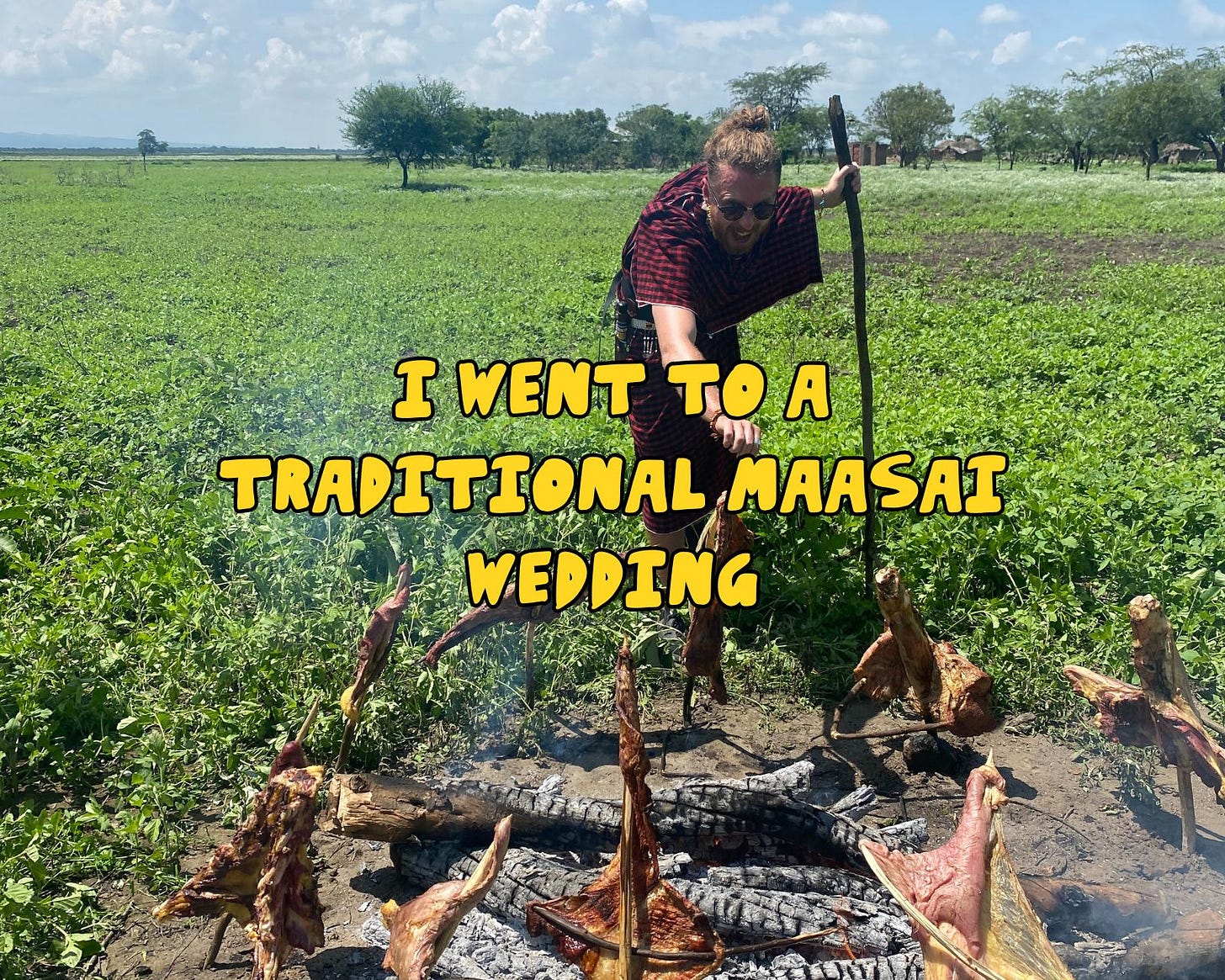

After the naming ceremony, I get on the back of Laizer’s bike and we rode across the plains towards the blue mountains (an area known primarily for the mining of Tanzanite). We pull up at smaller village surrounded by larger fences. They tell me its because they have a hyena problem in this area. A wedding is taking place in the afternoon and all of the men and women of the village are preparing for it. As is customary the men cook far away from the women. They have sacrificed several goats and are roasting them around a central fire. There are also large pots of rice and beans boiling away on a seperate fire.

The sun is brutally hot and there is little shade in this region. I’m introduced to various people from different tribes, most of whom don’t speak any english. I relay my basic pleasantries in Maa (the Maasai dialect).

“Supai” (hello - masculine)

“Epa” (Response to Supai - masculine)

“Keyaa” (What’s up - used only to men my age or younger)

I sit under the shade of a large tree. There are several dogs laying in the brush. A bunch of younger warriors are revving their motorbike and quite obviously talking about me. We eat miscellaneous chunks of goat meat with a large portion of rice cooked in oil. I eat around what I can only assume is the spine of a small goat who just this morning would have been running around the outskirts of the boma. The Baba’s nap on the empty bags of rice, while the other men drink sodas.

Soda is incredibly popular amongst the Maasai and in Tanzania in general. It’s all served in glass bottles and its customary to bring a case with you when you attend a wedding.

I drink a Stoney Tangawizi, a sweet and spicy ginger beer that’s incredibly popular in East Africa. I speak to a younger Maasai man who is wearing jeans and a t-shirt. He wants to go to university and get educated so that he can leave the village and find work. He’s hoping to work on his english as well.

The younger generation appears to be striving for a life beyond the confines of the boma, but many of their elders put pressure on them to uphold a traditional lifestyle. This becomes harder and harder to maintain as costs rise, and external factors like drought and government land “buy-backs” (pronounced stealing) make their lifestyle financially unsustainable. The Maasai are one of the only tribal cultures that have been actively preserved in this region of the world, and yet its easy to see how even they may face difficulties in maintaining their cultural integrity and identity in the years to come.

The bride arrives in a beat up four wheel drive. She wears a brightly decorated dress and is covered in handmade jewellery. She is welcomed by by a parade of women who chant and sing as they escort her into the boma. The men sit under trees nearby, chatting and snuffing tobacco.

We climb back onto the motorbike and drive home. We’re squashed up against one another, three of us on the bike, with a case of empty soda bottles balancing between Laizer’s arms. My legs get thrashed by thorny bushes as we weave through dried up creek beds and grazing livestock.

I chase the children around the water well, pretending to be a monster. Before I know it there’s close to fifty kids tackling me and begging to be picked up and carried around the boma. We run and jump and chase and laugh. I feel like I too am a kid again. I breathe in both freedom and guilt free play. I see why they are so happy here (for the most part). There is always play, and there is always community. The women gather in their circles to cook and clean, the men chat around fires and plastic tables. They dance and they sing, coming together many times of the year in moments of shared celebration, consciously curating states of ritual ecstasy.

These states of ritual ecstasy are associated with all major points in one’s life. From birth to marriage to death and everything in between. For men the most important is around their fifteenth birthday where they are ritually circumcised and inducted into manhood. I can’t help but feel like this moments of shared experience facilitate deep communal bonds, and clear markers of meaning in ones life. Purpose is given to individuals and communities through these rituals that mark a culturally aligned passageway through time. These major milestones also mark moments of connection between the generations, allowing young men and women to learn from their elders and vice versa. Something I feel like has been very much lost in contemporary western society.

As the sun sets, we make our way into town. There’s a bustling market full of fresh fruit and vegetables, recycled clothes and the iconic Maasai footwear - sandals made from the tyres of motorbikes. We buy some potatoes, tomatoes, fruit and spices. I come to learn a new name amongst the locals here - The mzungu Maasai.

Mzungu is a term used for foreigners, often white people across East Africa. Being the only white person in the market and one of the only white people to be living (and dressing) like the Maasai in the region I drew a lot of attention.

The dying hours of the afternoon are spent at a dishevelled local bar with poor service and cheap drinks. We play several rounds of pool and drink Konyagi, a cane liquor that Gilbert is particularly fond of. I realise quickly that Gilbert is a local legend in both Konyagi consumption and pool. The more he drinks the better he gets. I surrender after a few games, and spend the rest of the evening just observing the comings and goings of the bar itself.

Alcohol has been a part of Maasai culture for generations, but only for very specific ceremonies. In these cases it is a home-brewed concoction and often heavily regulated by the community. In recent times the introduction of external alcohol sources into these communities has brought about some issues. It’s still very rare to see alcohol brought into the boma itself (it would never be publicly declared nor displayed, especially in front of the women), but at the local bars it does appear to draw a crowd.

Most people I met at the various bars during my time with the Maasai (and I spent a fair amount of time at bars) were quick to ask me for drinks. If I declined they would negotiate with Gilbert for the same offering, deducting that I would be covering the tab for the both of us. In the most difficult of these situations I had drunk men seeing who could jump the highest in return for a beer or small bottle of gin. I never quite felt comfortable in these environments but somehow we always ended up there after a day in the sun. Drinking most often resulted in slurred conversations, excessive handshakes and a somewhat depressing atmosphere. I couldn’t help but feel overwhelmed with empathy, knowing full well that there was an unarticulated suffering sitting beneath all of this.

I really struggled with this aspect of my experience for the first few days of my stay, but ultimately forced myself to accept it as I had done in many other parts of the world with unsavoury drinking practices. I learned to be present and simply observe these men with empathy and kindness. I never offered to buy drinks, but inevitably would see their tabs added to mine at the end of the evening. Out of respect for my hosts I never argued.

The following morning I wake up early and catch a brief moment of solitude as the clouds part and reveal an epic sunrise around the edges of Mt. Kilimanjaro. I can tangibly feel my mind trying to comprehend a reality that seems so foreign to all that I know. I am wrestling with myself in a way that I have never quite experienced before. It’s all so profoundly intense and yet somehow there is a sensation of peacefulness that exudes out of the simplicity of survival. Everyone is so full of smiles and laughter. The lightness is intoxicating. Where is this back home? Where is such light-hearted presence?

We drink tea with a man whose wife is suffering from cancer. I don’t understand anything he says but I can sense the somber mood. I watch a sheep give birth and then proceed to wrestle with it and other livestock to receive their yearly vaccinations. Anthrax doesn’t sound like a great thing for livestock nor humans. We follow this up with a spray for ticks and fleas. It gets in my eye and I have to wash it out at a nearby water tap. The part of my brain rigged for anxious thoughts decides that I am going to go blind, but I do my best to silence his beckoning call.

We sit and drink more tea with the visiting doctors who provided the vaccinations. We talk about education and community bonds, while the children climb over my legs and shoulders. They take turns holding my hands as we walk from mud hut to mud hut.

Baba Glory, a particularly energetic and comedic character, has had an accident on his motorbike. His head is bruised and covered in blood and I imagine he is suffering from quite a severe concussion. We bring him tea and every laughs with him. He’s up and working in the fields by the afternoon. There is little time for rest. The harshness of life here hits me with one foul swoop. I feel guilty for all the times I have whinged and complained. I recognise how lucky I am. I feel the privilege of my passport, my currency and my skin.

I spend the next two days herding livestock and walking along the river. I meet many more members of the village and begin learning the greetings for women, as well as new phrases to expand my conversational abilities.

“Yeyo, Takwenya” - (greeting for singular female)

“Nooyeyo endakwenya” - (greeting for multiple women)

Rituals of conversation begin to form between me and various members of the community. I always greet the women fetching water in the morning and they ask where I am going for the day. The elder women always ask me my father’s name and I reply “Ola Barry”.

The Maasai have a Patronymic naming system, which basically means your given name is followed by your fathers name. Your status in the society is often associated with who your father is or was.

This becomes quite a comedic “bit” between me and many members of the community, as “Barry” is obviously a very uncommon name amongst the Maasai. Many of the young children find it so funny that they begin reply to their own requests for lineage with “Ola Barry”. I guess it’s one of those “had to be there,” situations, but trust me, it was quite funny hearing twenty Maasai children telling their elders that their father’s name was Barry.

I spend the afternoon walking with Beatrice (a nine year old girl bubbling with curiosity) and Saitoti (Gilbert’s two year old son who is the physical manifestation of sunshine). We follow Marcus (An old and deeply at peace mutt who I have a particular fondness for) along the railway tracks. The sky is painted with cascading colours of lilac and deep pink. Beatrice and I laugh about how different my life is back home in Australia. We say hello to farmers who are spraying their crops and watch women wash clothes in the river. I am filled with a familiar sense of awe. That kind of awe that starts in your fingertips and vibrates up along your arms and into your chest. It’s like a culmination of peace, curiosity and gratitude moving down your spine with the texture and pace of sand.

I smile and the moon appears. I feel at home here. It’s strange and difficult, confronting and beautiful.

Time moves slow and yet somehow quickly. I am present in all that I am doing, but the overwhelming newness of every moment creates a tapestry of moments that are rapidly sewn together to form an ever moving blanket. I have the space to admire the stitching and yet not enough capacity to adequately connect all the disparate parts nor wrap myself in its warmth. I guess this is a good thing though; it’s bloody hot.

More to come…

Stay Weird,

Zed